After 30 years’ experimentation, farmers in Washington state are ready for the biggest ever planting of a new variety of apple.

Nearly 30 years ago, Dr Bruce Barritt was jeered when he branded the apple industry in Washington state a dinosaur for growing obsolete varieties such as red and golden delicious. Now, farmers in the state, where 70% of US apples are grown, are ripping up millions of trees and replacing them with a new variety, the cosmic crisp, which Barritt, a horticulturalist, has created in the decades since.

HOW DO YOU LIKE THEM APPLES? LEAD SCIENTIST DR KATE EVANS AT WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY’S TREE FRUIT RESEARCH & EXTENSION CENTER. PHOTOGRAPH: TED S. WARREN/AP

With 12m trees to be planted by 2020, and the first harvest of apples due in the shops in 2019, it is the biggest ever launch of a new apple. Around 10m 40lb boxes are expected to be produced in the next four years, compared with the usual 3-5m for anew variety. It’s a gamble for growers: replanting costs up to $50,000 per acre, so the cosmic crisp needs to fetch top dollar to make their investment worthwhile.

Barritt began his quest for the perfect apple in the 1980s, after being hired by Washington State University (WSU).

“I had two projects,” he says. “The orchards being grown were inefficient – big trees that required ladders, poor fruit quality because of shade in the trees… That was a problem I could tackle. But I thought the most important problem was that, at the time in Washington, 90% of the crop was red delicious and golden delicious – they’re not crisp, juicy or flavourful. I was giving a talk to 2,000 industry people and I told them these were obsolete. It didn’t go down well. If I asked them why they were still growing these varieties, they’d say ‘Because we grow them better than anybody else.’ That wasn’t good enough, because the consumer wasn’t happy.”

Barritt was convinced better varieties had to be developed, and made available to every farmer in the state (new varieties such as jazz and ambrosia are often only licensed to small clubs of growers). He spent six years lobbying the industry in Washington and the university for money to fund a breeding programme, which began in 1994.

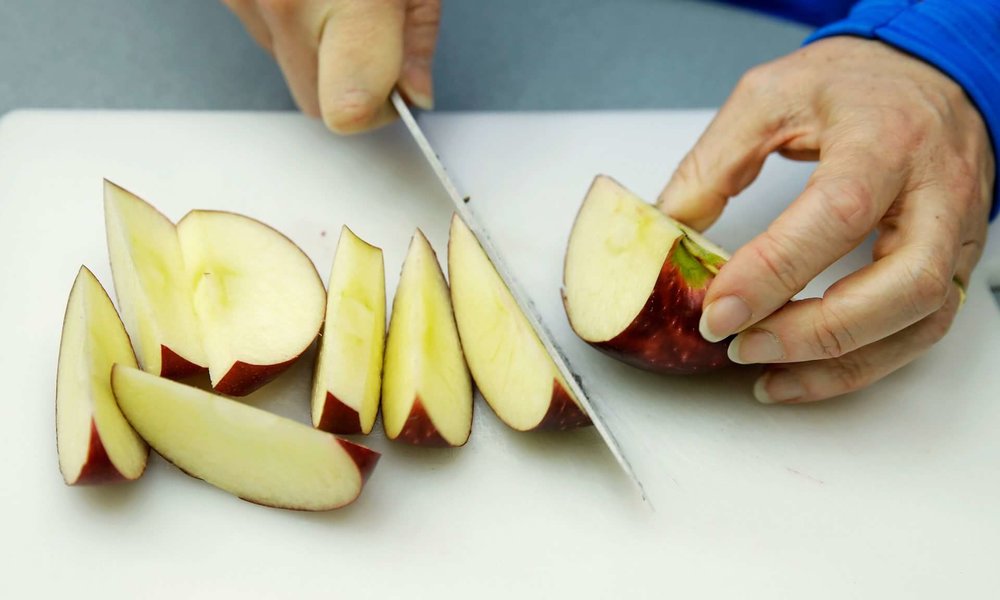

SWEET BUT NOT TOO SWEET. PROOF IS IN THE TASTING FOR THE COSMIC CRISP. PHOTOGRAPH: TED S WARREN/AP

“It’s a traditional breeding programme, not genetically modified; it’s hybridising existing varieties,” he explains. “All the traits important in an apple – the flavour, juiciness, crispness – are controlled by many genes. Our knowledge of genetics is not good enough to collect all those genes together and change them with genetic modification.”

Barritt created thousands of seedlings by cross-pollinating the blossoms of parent trees. “When they come into bearing, we walk the long rows and bite, chew and spit, because you can’t eat a lot of apples at once – your taste buds lose their sensitivity. The majority you bite into are terrible, but eventually you come up with ones that are good.”

The cosmic crisp, so named because of its yellow star-like flecks on a burgundy skin, is a cross between the honeycrisp and the enterprise. “Honeycrisp’s claim to fame is its crispness; it also has good sugar and acid and texture. Enterprise is large, full-coloured, stores well and is firm. It’s got good acidity and flavour in general.” Enterprise is also known for its resistance to fire blight.

The tree selected was known as WA38. “It was promising, so we made 15 trees and planted those in three locations in central Washington, and looked at those for three or four years of fruiting. We still liked it, so we made 200 trees of the same one and planted it in four sites in commercial orchards. We wanted to see how they performed in the hands of growers.”

Around this time, Barritt retired. Dr Kate Evans, a British horticulturalist who had been leading breeding programmes for East Malling Research in Kent, took over.

Testing of the apple continued and it was patented in 2014, with Barritt named as the “inventor”. For the next 10 years, it will only be available to US farmers in Washington, because they helped fund the breeding programme.

Evans said: “Outside the US, new varieties go through a variety rights application – you test them in different locations and compare them to varieties out there so that it can be seen they’re different and novel. In the US they don’t do that; it’s a plant patent system – like [with] any other invention, you submit an application that describes it in detail.”

Every cosmic crisp tree is a clone of the WA38 “mother tree”, which remains in WSU’s research orchard near Wenatchee. Buds from one tree are grafted on to existing apple tree roots. These buds grow into copies of the original tree.

To meet demand, nurseries are reproducing the trees on a massive scale. This year, there were only 600,000 available, which were allocated to growers using a draw.

Stemilt Growers, a fruit company in Wenatchee, has planted 180,000 trees. Its president, West Mathison, said: “The apple has got great flavour. The crunch is really consistent. There’s more strength in the connective tissue of the cells than the cell walls themselves, so your teeth break through the cells and flavour, and juice is released. It has a unique flavour – sweet but not too sweet, and a little bit of acid, so it has some complexity. It’s also got a really nice storage life. I’m planting it on an old golden delicious block. Red and golden are falling out of favour with the market,” Mathison said. “It’s definitely a gamble. We don’t know yet what the retail price will be.”

Barritt, however, is confident the apple will be a winner. “This variety has been tested in the research setting, in grower orchards, in cold storage and with consumers more than any other apple in the world,” he says. “I’m not nervous.”

Article by Lucy Rock, The Guardian